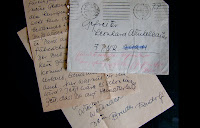

This is an excerpt of a short memoir written by my great aunt, who experienced the war both in Bohemia and Vienna. Schloss Friedland still stands in Northern Bohemia, described here as the Sudetenland. In 1945, the family lost all of their property in Bohemia. The picture on the left shows the family house in Vienna. Today it is the French Cultural Institute, at Währingerstrasse 30.

In 1938 our mother died. Very soon after that came the “Liberation of the Ostmark”, as well as the “Liberation of the Sudetenlands”

A planned visit of the so-called Führer at Schloss Friedland went by the wayside at the last minute. Thereby luckily sparing Herr von Papen a visit with him in the castle. Herr von Papen and his Silesien neighbor arrived that day when Hitler was in the town of Friedland. During the war military quarters were allocated in the castle. This was the staff of the local operations regiment. It worked quite well for us and wasn’t problematic. Once the bombing of Berlin started, the contents of the Berlin Library were brought to us for safekeeping. I was in Friedland for the last time shortly before Christmas 1944. Thereafter I no longer received papers for traveling there from Vienna on the basis that I was required to stay in the city for the purposes of “air raid security”.

The cellar of our large house in Vienna was used as a public air raid shelter for part of the city. My sister Edina and I functioned on an ad hoc basis there as hostessess. Those who came to the cellar became with the passing of time and the dropping of bombs a real community. Once the Palais avoided being blown up by sheer miracle. A carpet bombing raid dropped bombs to the front and the side of the house. The wing of a neighboring house was destroyed. Beneath the sloping of the house down to the lower garden the cellar extended expansively below. This also functioned as an air raid shelter--people came there from Floridsdorf. There was room for 10,000 people in these cellars, which had an enormous number of branching tunnels, and had originally been used for raising mushrooms. It was a time of great sadness and fear but redeemed itself for the goodness experienced in being able to help people, whose lives were endangered by the war. This brought me into contact with many wonderful people. In particular I recall the unwaveringly brave Deacon P Bruno Spitzl, as well as the quietly courageous Etta Matscheko. Etta fell victim to a bomb attack later.

In the very last days of the war a first aid station opened up in the Palais, with a young staff doctor, Dr Wiesner (now a pediatrician) in charge. There were ten officers and 50 staff. This was to a certain extent a stroke of luck, because later when an SS group marched into the garden, they found it was already occupied and had to move on. During the days of the war when Vienna was actually under attack, the Palais and the the little house in Botlzmangasse 2 took two grenade hits, which in comparison to the bombs that were later dropped by the Americans, were not very significant. A German tank stood at the garden fence of the Währingerstrasse--later it was a Russian Stalinorgel.

There were several automatic weapon installations located around the house and on the flat roof of the kitchen area. In those days we shared everything--both good and bad-- with those poor souls who found themselves in our care as a result of the bombing: the pharmacist couple known as the Dormanns, the brother and sister pair Leo and Helene Schreiner (he was a civil servant, she a doctor), and a Polish family, who arrived in an appallingly filthy state, Gräfin Sophie Skarbek and her two sons. Gradually others found their way to us for protection and support. A great help to us in this time, and through the rest of their lives, were the two sisters Marie and Annerl Erger. Even in the most trying moments of the war, they never let us down. They suffered a great deal with our family, and all people whose flight through a war torn city brought them to us, always found themselves in caring hands.

The first aid unit that had been with us moved over the Danube, but became a useful source of food as they left provisions behind. We spent most nights in the cellar sheltering from bombs. We kept watch for the sake of precaution. Generally my sister Edina and I went through the house. First we feared the SS, later we feared the Russians. Then, the dreadful work of having to help bury the dead from local bombing raids in the garden. There were Italian workers, who were there to help, who asked to be given shelter in the house. They were memorable for the fuss they made the instant they sensed Russians nearby--it was like the capitoline geese raising the honking alarm.

There was considerable excitement involved in the removal of ordinance from the house--weapons, ammunition, hand grenades. Handling them, in particular the latter of these, was always tricky as we were never sure whether they might accidentally go off! Our lives returned--only very slowly--to some sort of normality. An unforgettable event amidst all this was a concert of the Philharmonic Orchestra on the 29th of April 1945. Food continued to be scarce for a long time however, and we were thankful for every little vegetable that grew in our garden. Sometimes half starved cows were driven into the garden by Russians with an eye to slaughter, who then took to my lovingly tended vegetable garden.

We were so excited to see the first cars of the Swiss Red Cross in Vienna. They stood lined up in the park, white and clean (something all but forgotten to us), and seemed to us to have arrived from another happier world entirely. With great gratitude we also received packages from the von Trapp family, sent over to us from America. We were able to help many with the things they sent us.

Because it was the Americans who had had taken over from the Russians in our Bezirk, it was decided that our house should be handed over for use as a US Service Club for officers--this however after a great “resistance” fight! Our house thus fell to the fate of all the others that were “used” by occupying forces. Mrs Eleanor Dulles, who had earlier been director of a civilian unit and lived with us, found to her irritation that she, too, had to yield to the arrival of the US officers. And so it was that we moved out of our family home with heavy hearts. It was at just this time that the Podstatzkys, destitute and hungry, arrived in Vienna in the hope of finding a quiet and safe harbour in the Währingerstrasse.